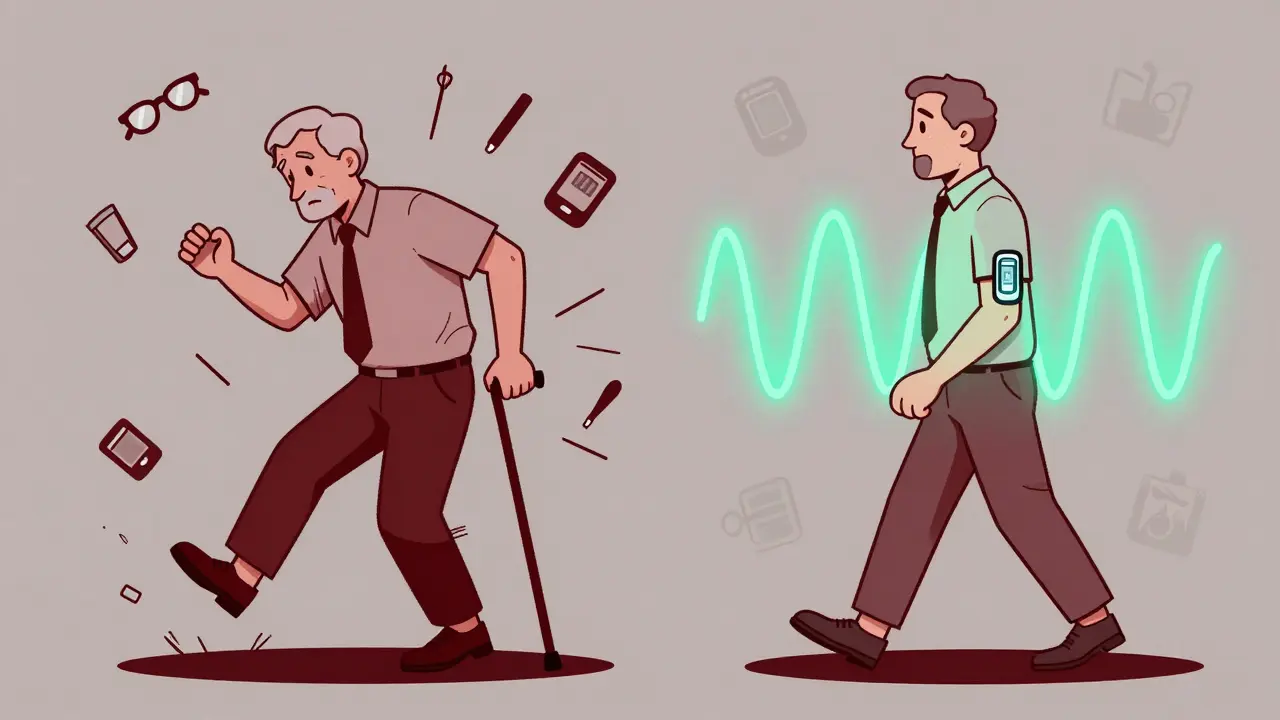

For many seniors living with diabetes, the biggest danger isn't high blood sugar-it's low blood sugar. Hypoglycemia, or blood glucose below 70 mg/dL, is far more common and far more dangerous in older adults than in younger people. It can lead to falls, confusion, heart problems, and even death. The truth is, some of the most commonly prescribed diabetes medications for seniors actually increase this risk. The good news? There are safer options-and simple steps you can take to protect yourself or a loved one.

Why Seniors Are at Higher Risk for Low Blood Sugar

As we age, our bodies change in ways that make managing blood sugar harder. Kidneys don’t filter drugs as well, so medications like glyburide stick around longer in the system. The body’s natural defenses against low blood sugar-like releasing adrenaline to raise glucose-become weaker. Many seniors also take multiple medications for other conditions, which can interact with diabetes drugs and make hypoglycemia more likely.One in four Americans over 65 has diabetes. And studies show they experience low blood sugar 2 to 3 times more often than younger adults. Even a single severe episode-where someone needs help from another person-can raise the risk of dying within a year by 60%. That’s not just a statistic. It’s why doctors now say: for seniors, avoiding low blood sugar matters more than hitting a perfect HbA1c number.

Medications That Put Seniors at Risk

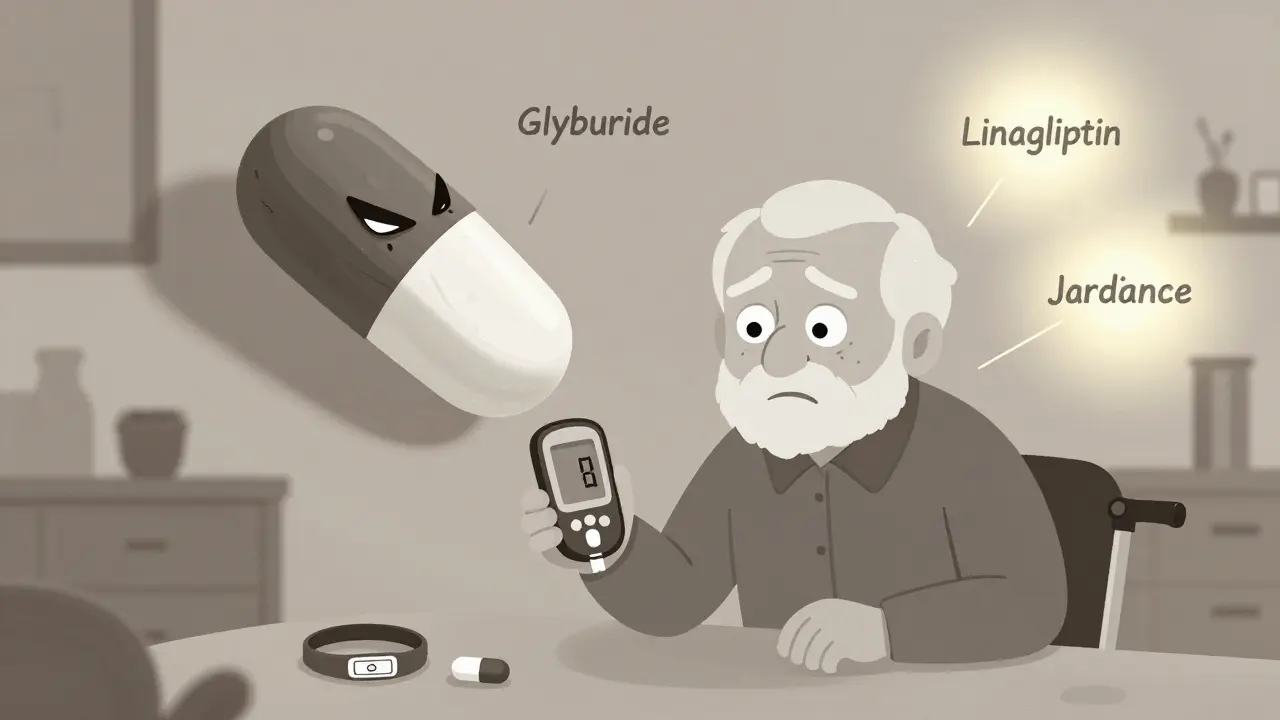

Not all diabetes pills and injections are created equal when it comes to safety. Some are fine. Others? They’re dangerous for older adults.Glyburide (brand names: Glynase, Micronase) is one of the worst offenders. It’s a sulfonylurea, a type of pill that forces the pancreas to pump out more insulin. The problem? It lasts too long in the body. In seniors with slower kidneys, it can cause low blood sugar that lasts for hours-even overnight. Studies show nearly 40% of elderly patients on glyburide have at least one hypoglycemic episode per year. The American Geriatrics Society explicitly says: avoid glyburide in older adults.

Glipizide (Glucotrol) is another sulfonylurea, but it’s shorter-acting and cleared by the liver instead of the kidneys. That makes it safer than glyburide-but still not ideal. About 20% of seniors on glipizide still get low blood sugar. It’s a step up, but not a safe long-term choice.

Insulin, especially long-acting types like Lantus or Levemir, is another major risk. It doesn’t adjust automatically. If a senior skips a meal, walks more than usual, or gets sick, their blood sugar can crash. Research shows insulin use increases fall risk by 30% in older adults because of dizziness and weakness from low sugar.

Safer Alternatives for Seniors

The good news is that newer medications offer strong blood sugar control with almost no risk of low blood sugar when used alone.DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin (Januvia), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and saxagliptin (Onglyza) work by helping the body use its own insulin more efficiently. They don’t force insulin production. As a result, hypoglycemia rates are only 2-5%-compared to 30-40% with glyburide. Linagliptin is especially convenient because it doesn’t need dose adjustments for kidney problems, which is common in seniors.

SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) work by making the kidneys flush out extra sugar through urine. They rarely cause low blood sugar unless taken with insulin or sulfonylureas. In clinical trials, hypoglycemia rates were under 5%. Plus, they help with heart health and weight loss-two big wins for older adults.

Metformin is still the first-line treatment for many, but it needs careful use. It doesn’t cause low blood sugar on its own. But if kidney function drops below 30 mL/min (measured by creatinine clearance), it can build up in the body and cause lactic acidosis. Many doctors stop metformin in patients over 80 or those with advanced kidney disease. Regular blood tests are a must.

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro), a newer injectable approved in 2022, has shown only 1.8% hypoglycemia rates in elderly patients-far lower than insulin. It’s not yet widely used in seniors due to cost and side effects like nausea, but it’s a promising option for those who need stronger control without the risk.

What to Do If You’re on a High-Risk Medication

If you or someone you care for is taking glyburide or another high-risk drug, don’t panic-but do act.First, talk to the doctor. Ask: Is this the safest option for me right now? Many seniors have been on glyburide for years without realizing there’s a better choice. A simple switch to linagliptin or sitagliptin can make all the difference.

Real stories prove it. Mary Thompson, 78, had three falls in six months from low blood sugar on glyburide. After switching to sitagliptin, she had zero episodes in six months. "I can walk to the mailbox without fear," she says.

Another patient, an 82-year-old man on glipizide, kept waking up confused and sweaty at night. His caregiver noticed his blood sugar was dipping below 50 mg/dL. Switching to linagliptin stabilized his levels between 90-140. No more nighttime crashes.

Don’t stop medication on your own. But do ask for a medication review. Pharmacists can help spot dangerous combinations-like beta-blockers hiding low sugar symptoms, or NSAIDs boosting sulfonylurea effects. The STOPP/START criteria, used by geriatric specialists, help identify which drugs to remove or add. Studies show using this method cuts hypoglycemia hospitalizations by 32%.

Monitoring and Prevention Strategies

Even with safer meds, vigilance matters.Learn the signs of low blood sugar: dizziness, sweating, shaking, hunger, confusion, fast heartbeat, weakness. These can be mistaken for aging or fatigue. If you feel any of these, check your blood sugar immediately. Don’t wait.

Keep fast-acting sugar handy-glucose tablets, juice boxes, or even hard candy. Tell family or caregivers what to do if you can’t treat yourself. Some seniors benefit from a medical alert bracelet that says "Diabetic-risk of low blood sugar."

Consider a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). These devices, worn like a patch, track sugar levels all day and night. For seniors, they’re a game-changer. One study found CGM users over 65 had 65% fewer low blood sugar events than those using fingersticks. Many Medicare plans now cover CGMs for high-risk patients.

Check blood sugar before meals, before bed, and if you feel off. Don’t assume you’ll feel it coming. Many seniors lose the warning signs over time.

When to Get Help

If someone with diabetes becomes confused, has a seizure, or passes out from low blood sugar, call 911. Glucagon injections are available by prescription and can reverse severe hypoglycemia. Make sure a family member knows how to use it.Emergency visits for diabetes-related low blood sugar are the leading cause of hospital trips for seniors on Medicare. In 2022, nearly 3 out of 10 diabetes-related ER visits were due to hypoglycemia. Most were from sulfonylureas or insulin.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Schedule a medication review every 3-6 months. Ask your doctor: "What’s my biggest risk right now? Is this medication still the best choice?" The goal isn’t perfection-it’s safety. Stable, slightly higher blood sugar is better than a dangerous drop.

Final Thoughts

Managing diabetes in seniors isn’t about chasing the lowest possible HbA1c. It’s about living well, staying independent, and avoiding falls and hospital stays. The right medication can make that possible.Stop accepting "this is just how it is" when it comes to low blood sugar. There are safer, smarter options. Talk to your doctor. Ask questions. Advocate for yourself or your loved one. Your next meal, your next walk, your next night’s sleep-those matter more than a number on a lab report.

What diabetes meds are safest for seniors?

The safest options for seniors are DPP-4 inhibitors like sitagliptin (Januvia) and linagliptin (Tradjenta), and SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance). These rarely cause low blood sugar when used alone. Metformin is also safe if kidney function is normal. Avoid glyburide and long-acting insulin unless absolutely necessary.

Why is glyburide dangerous for older adults?

Glyburide has a long half-life and is cleared by the kidneys. As people age, kidney function declines, so the drug builds up in the body. This can cause prolonged, unpredictable low blood sugar-even hours after eating or during sleep. Studies show nearly 40% of seniors on glyburide have at least one hypoglycemic episode per year. The American Geriatrics Society lists it as a medication to avoid in older adults.

Can metformin cause low blood sugar in seniors?

No, metformin alone does not cause hypoglycemia. But it’s not safe for everyone. If kidney function drops below 30 mL/min, metformin can build up and cause a rare but serious condition called lactic acidosis. Seniors over 80 or with chronic kidney disease should have their creatinine clearance tested regularly. Many doctors stop metformin in these cases.

What should I do if I suspect low blood sugar?

Check your blood sugar right away. If it’s below 70 mg/dL, consume 15 grams of fast-acting sugar: 4 glucose tablets, ½ cup of juice, or 1 tablespoon of honey. Wait 15 minutes, then check again. If it’s still low, repeat. If you’re confused, unable to swallow, or unconscious, someone must give you glucagon or call 911. Never try to give food or drink to an unconscious person.

Is a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) worth it for seniors?

Yes-especially if you’ve had low blood sugar episodes before, take insulin, or live alone. CGMs track sugar levels 24/7 and alert you to drops before they become dangerous. One study found seniors using CGMs had 65% fewer hypoglycemic events than those using fingersticks. Many Medicare plans now cover CGMs for high-risk patients. It’s one of the most effective tools for preventing falls and hospital visits.

How often should seniors have their diabetes meds reviewed?

Every 3 to 6 months. Medications, kidney function, and overall health change over time. A pharmacist or doctor should review all prescriptions-including over-the-counter drugs and supplements-to catch interactions and outdated prescriptions. The American Diabetes Association recommends structured medication reviews for all seniors with diabetes to reduce hypoglycemia risk.

Comments (15)