When you switch to a generic drug, you expect the same effect as the brand-name version. But what if your body doesn’t respond the same way - not because the pill is different, but because of your genes? This isn’t rare. For many people, family history and genetic makeup determine whether a generic medication works, causes side effects, or does nothing at all. The truth is, two people taking the exact same generic drug can have completely different outcomes - one feels better, the other ends up in the hospital. And it’s not about dosage or quality. It’s about your DNA.

Why Your Genes Decide If a Generic Drug Works

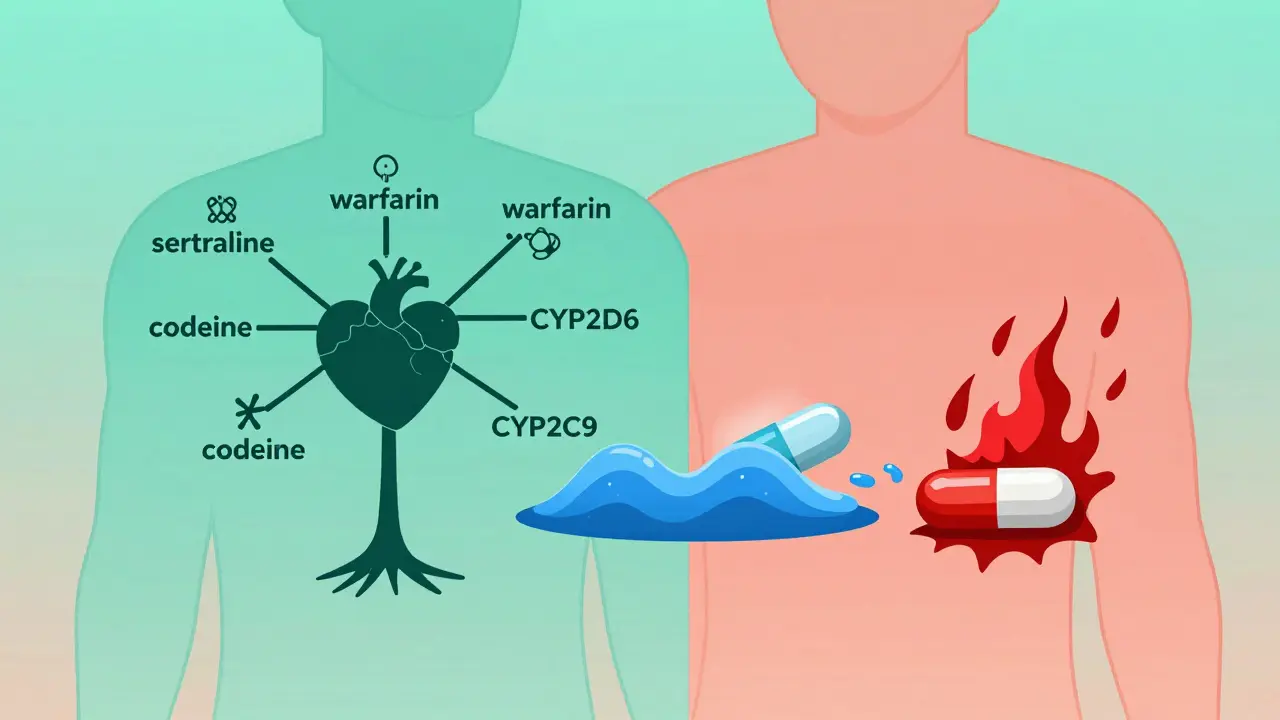

Your body uses enzymes to break down medications. One of the most important enzyme families is called cytochrome P450, especially the CYP2D6 gene. This gene is responsible for processing about 25% of all prescription drugs - including common ones like antidepressants, beta-blockers, and pain relievers. But here’s the catch: CYP2D6 isn’t the same for everyone. More than 80 genetic variants exist worldwide, and they turn you into a poor, intermediate, normal, rapid, or ultra-rapid metabolizer. If you’re a poor metabolizer, your body can’t break down the drug fast enough. That means the drug builds up in your system, leading to toxic side effects. If you’re an ultra-rapid metabolizer, your body clears the drug too quickly - so it never reaches the level needed to help you. This is why two people on the same generic sertraline might have opposite results: one feels calm, the other feels anxious or nauseous. And if your parent had a bad reaction to the same drug, you’re more likely to too.Family History Isn’t Just a Story - It’s a Warning Sign

When your doctor asks about your family’s medical history, they’re not just being thorough. They’re looking for clues your genes already gave away. If your mother had severe side effects from a generic statin, or your brother needed a higher dose of warfarin to prevent clots, that’s not coincidence. It’s inheritance. Take warfarin, a blood thinner commonly prescribed after heart surgery or stroke. The FDA now recommends genetic testing before starting it. Why? Because variants in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes control how much warfarin your body needs. African Americans, on average, require higher doses than Europeans - not because of weight or diet, but because of common genetic differences. If your family is from West Africa, and you’ve never been tested, you’re at higher risk of bleeding or clotting if dosed the same way as someone with European ancestry. The same goes for clopidogrel (Plavix), a generic antiplatelet drug. About 30% of Asians carry a variant in CYP2C19 that makes the drug ineffective. If your family has roots in Southeast Asia and you’ve had a heart attack, taking the generic version without testing could mean your next heart attack is just around the corner.Genes That Can Kill - And How to Find Them

Some gene-drug interactions are life-threatening. The TPMT gene controls how your body handles thiopurines - drugs used for leukemia, Crohn’s disease, and autoimmune disorders. If you have two faulty copies of TPMT, even a standard dose can destroy your bone marrow. Before 2005, doctors didn’t test for this. Now, pediatric oncology units test every child before starting treatment. The result? Severe side effects dropped by 90%. Another example is DPYD. This gene breaks down 5-fluorouracil, a chemotherapy drug. If you have a rare variant, even a small dose can cause deadly diarrhea, mouth sores, and low blood counts. A patient in Cape Town shared her story: after her Color Health test flagged a DPYD variant, her oncologist cut her dose by 33%. She finished treatment without hospitalization. Without the test, she might not have made it. These aren’t edge cases. In a 2023 Mayo Clinic study of 10,000 patients who got preemptive genetic testing, 42% had at least one high-risk gene-drug interaction. Two-thirds of those patients had their meds changed - and adverse events dropped by 34%.

Why Generic Drugs Don’t Always Mean the Same Results

Generic drugs are required to have the same active ingredient as brand-name versions. But they’re not required to be identical in how your body handles them. That’s because generics are approved based on average response - not individual genetics. A 2022 study in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology found that patients switching from brand to generic antidepressants were 22% more likely to report side effects or relapse - not because the generic was inferior, but because their genetic profile wasn’t considered. One patient in Johannesburg switched from brand sertraline to a generic version after her insurance denied coverage. Within weeks, she developed serotonin syndrome. Her pharmacist didn’t know she was a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Her doctor didn’t ask about her father’s history of bad reactions to SSRIs. The problem isn’t the generic. It’s the assumption that all bodies process drugs the same way.What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need a PhD or a fancy lab to protect yourself. Here’s what works:- Know your family’s drug history. Did anyone in your family have a bad reaction to a medication? Write it down - name, drug, side effect. Bring it to every doctor visit.

- Ask if your drug has a pharmacogenetic label. Over 300 drugs, including warfarin, clopidogrel, codeine, and certain antidepressants, have FDA guidance on genetic testing. Check the label or ask your pharmacist.

- Consider a one-time genetic test. Tests from companies like Color Genomics or OneOme cost $250-$500 and screen for 15-20 key genes. They’re not covered by all insurers yet, but Medicare now pays for some tests if you’re on high-risk meds.

- Use PharmGKB or CPIC guidelines. These free, science-backed resources tell doctors what to do based on your genes. Ask if your provider checks them.

The Reality: Testing Isn’t Everywhere - But It’s Getting There

In academic hospitals in Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Pretoria, pharmacogenetic testing is becoming standard for oncology and psychiatry. But in community clinics? Still rare. A 2023 survey found only 32% of South African community hospitals offer any form of genetic drug testing. The biggest barrier? Time. Doctors are overwhelmed. A 2022 survey of 450 GPs showed 79% wanted genetic decision tools built into their electronic records - but only 12% had them. Epic Systems, the biggest EHR provider, added CPIC alerts for 12 high-risk gene-drug pairs in 2022. But most clinics still don’t use them. Still, change is coming. The NIH spent $127 million in 2023 on pharmacogenomics research - especially for underrepresented populations like Africans and Indigenous groups. The All of Us program aims to return genetic results to 1 million people by 2026. And South African universities are starting pilot programs to integrate testing into primary care.What Happens If You Ignore It?

Ignoring genetics isn’t harmless. It’s like driving with blinders on. You might get lucky - but the cost of a mistake can be fatal. A man in Durban switched to a generic codeine after surgery. He was an ultra-rapid metabolizer - his body turned codeine into morphine too fast. He stopped breathing and needed emergency care. His family had no history of opioid reactions. He didn’t know his genes were the issue. The good news? You don’t need to wait for your doctor to act. You can start today. Ask your pharmacist: “Is this drug affected by genetics?” Check your family’s medication history. If you’ve had unexplained side effects, consider testing. Your genes didn’t ask for permission to affect your health. But you can ask for permission to understand them.Can generic drugs be less effective because of genetics?

Yes. Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient as brand-name versions, but your body’s ability to process them depends on your genes. For example, if you’re a poor metabolizer of CYP2D6, a generic antidepressant like sertraline may build up to toxic levels - even if the pill is identical. The drug isn’t weaker; your body handles it differently.

Does family history really matter for drug reactions?

Absolutely. If your parent, sibling, or child had a severe reaction to a medication - like liver damage from statins, bleeding from warfarin, or serotonin syndrome from SSRIs - you likely share the same genetic variants. Family history is one of the strongest predictors of how you’ll respond to a drug, even before testing.

What’s the most common gene that affects generic drug response?

The CYP2D6 gene is the most common. It affects about 25% of all prescription drugs, including painkillers, antidepressants, and beta-blockers. Over 80 variants exist, turning people into poor, normal, or ultra-rapid metabolizers. This gene alone explains why two people on the same generic pill can have opposite outcomes.

Are genetic tests for drug response covered by insurance in South Africa?

Most private insurers don’t cover pharmacogenetic tests yet. However, Medicare in the U.S. now covers certain tests for high-risk drugs like warfarin and clopidogrel. In South Africa, some medical schemes are beginning to cover testing for oncology and psychiatric medications, especially if your doctor documents a prior adverse reaction. Out-of-pocket tests cost between R4,500 and R9,000, depending on the panel.

Can I get tested before switching to a generic drug?

Yes - and it’s smart to do it. If you’re about to switch from a brand-name drug to a generic, especially for mental health, heart disease, or cancer treatment, ask your doctor for a pharmacogenetic test. Results can take 1-2 weeks. If your genes show you’re at risk, your provider can choose a different drug or adjust the dose before you even take the generic.

Comments (13)