Every year, millions of people get staph infections. Most are harmless. But when the bacteria become resistant to common antibiotics like penicillin and methicillin, you’re dealing with MRSA - Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. And here’s the thing: not all MRSA is the same. The strain you pick up at the gym isn’t the same as the one you catch in a hospital. They look different, behave differently, and need different treatments. Yet, the lines between them are blurring - fast.

What Makes MRSA Different From Regular Staph?

Staphylococcus aureus is everywhere. It lives on skin, in noses, sometimes without causing harm. But when it gets into a cut, a burn, or a surgical wound, it can turn dangerous. MRSA is the version that laughs at antibiotics most doctors reach for first. It’s not just resistant to methicillin - it shrugs off oxacillin, penicillin, and amoxicillin too. That’s why it’s called MRSA: Methicillin-Resistant.

Back in the 1960s, MRSA was almost always a hospital problem. Patients with weak immune systems, catheters, or open wounds were most at risk. But in the late 1990s, something unexpected happened. Healthy people - athletes, kids, military recruits - started getting serious MRSA infections without ever setting foot in a hospital. These were the first community-associated strains, or CA-MRSA.

CA-MRSA vs. HA-MRSA: The Genetic Divide

Genetically, CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA are like two different species wearing the same name. CA-MRSA carries a smaller piece of DNA called SCCmec type IV or V. This tiny package gives it just enough resistance to survive antibiotics, but it doesn’t carry extra weapons. Instead, it packs a punch with something called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). This toxin destroys white blood cells, leading to angry, fast-spreading skin infections or even deadly pneumonia.

HA-MRSA, on the other hand, carries larger SCCmec types (I, II, or III). These are like armored suits - they let the bacteria resist not just penicillin, but also clindamycin, erythromycin, and fluoroquinolones. That’s why HA-MRSA infections are harder to treat. In fact, over 90% of HA-MRSA strains are resistant to three or more antibiotic classes.

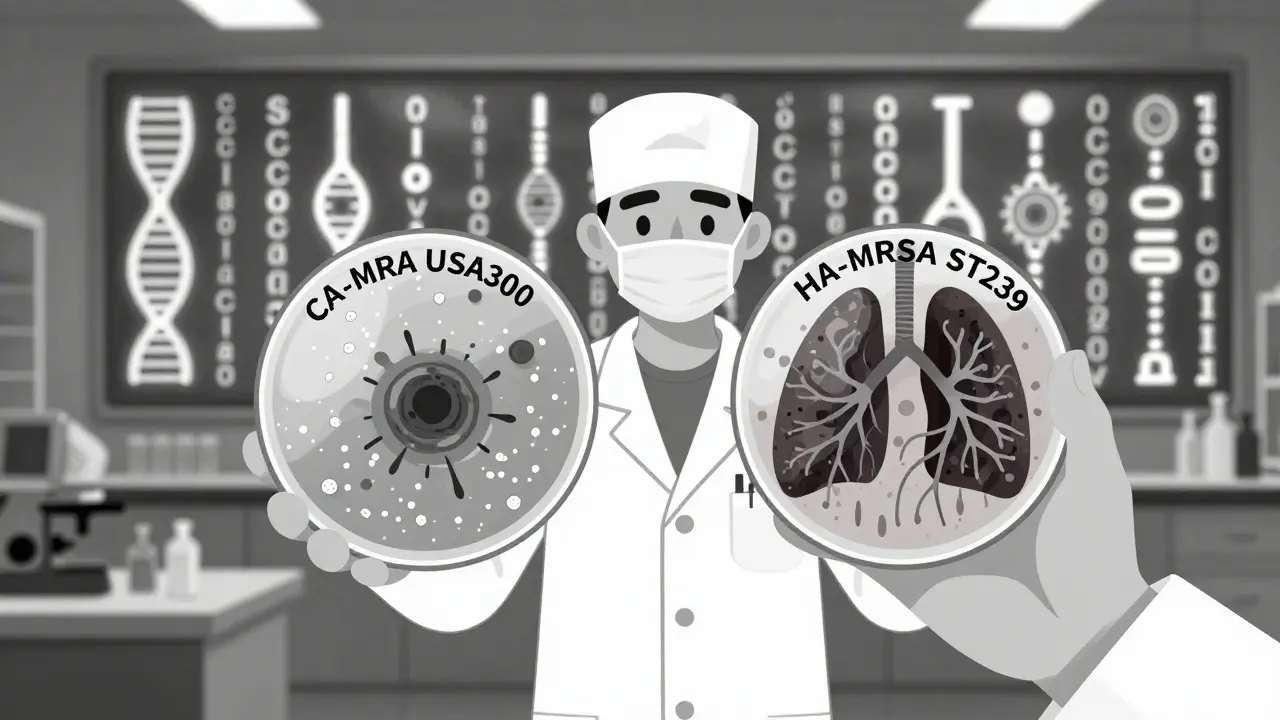

One strain, USA300, dominates the community. It’s responsible for about 70% of CA-MRSA cases in the U.S. It’s the one you’ll find in gyms, dorms, and prisons. Meanwhile, HA-MRSA strains like ST239 and ST59 are more common in hospitals - especially in Asia and parts of Europe.

Where You Get It: How Transmission Works

CA-MRSA spreads through skin-to-skin contact. Think wrestling, sharing towels, or touching a contaminated surface in a locker room. Crowded places make it worse. Military barracks? 12 times more likely to spread. Prisons? Nearly 15 times higher risk. Homeless shelters and subsidized housing? Also hotspots. Injecting drug users are a major reservoir - needle sharing, dirty skin, and poor hygiene turn their bodies into MRSA factories.

HA-MRSA spreads differently. It’s carried by healthcare workers, on equipment, or through open wounds during surgery or dialysis. A patient gets admitted, picks up MRSA from a bed rail or an IV line, and develops an infection days later. That’s called hospital-onset MRSA.

But here’s the twist: the two worlds are talking to each other. A 2017 Canadian study found that nearly 28% of hospital MRSA cases came from community strains. And 28% of community cases were caused by hospital strains. That means someone with a CA-MRSA skin infection might get admitted for another reason - and bring the strain inside. Or a hospital patient with HA-MRSA gets discharged, carries the bacteria home, and infects their family.

What the Infection Looks Like: Symptoms and Severity

Both types often start as a red, swollen, painful bump - like a spider bite or a pimple that won’t go away. But CA-MRSA tends to hit fast and hard. It causes abscesses, boils, and cellulitis. People usually show up at the ER with one or two bad sores. Hospital stays? On average, 2.8 days. Many just need the abscess drained - no antibiotics required.

HA-MRSA is sneakier. It doesn’t just sit on the skin. It goes deep. Pneumonia, bloodstream infections, bone infections - these are more common with HA-MRSA. Patients are often already sick. Their immune systems are down. Their bodies are full of tubes and wounds. Recovery takes weeks. Average hospital stay? Over 21 days.

One scary difference: CA-MRSA can cause necrotizing pneumonia - a rare, fast-killing lung infection. It’s rare, but when it happens, it’s usually tied to USA300. HA-MRSA rarely causes this. Instead, it causes sepsis, especially in older patients or those on dialysis.

Treatment: What Works and What Doesn’t

For CA-MRSA, the first line of defense is often just cutting open and draining the abscess. Antibiotics aren’t always needed. But if they are, clindamycin works in 96% of cases. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) works in 92%. Tetracyclines like doxycycline? 89% effective. These are old, cheap drugs - and they still work.

HA-MRSA? Not so simple. Because it’s resistant to so many drugs, doctors have to use stronger ones: vancomycin, daptomycin, or linezolid. These are expensive, need IV delivery, and can damage kidneys or nerves. And even then, some HA-MRSA strains are starting to resist vancomycin.

Here’s the problem: hospitals can’t assume all MRSA is HA-MRSA anymore. If a patient walks in with a skin infection and no recent hospital stay, but the strain turns out to be HA-MRSA, giving them clindamycin could fail. That’s why labs now do rapid genetic testing - not just to confirm MRSA, but to tell if it’s CA or HA type. Treatment depends on the strain, not just the setting.

The Blurring Line: Why Old Definitions Are Failing

The CDC’s old definition of CA-MRSA was simple: if you hadn’t been in a hospital, dialysis center, or nursing home in the past year, it’s community. But that doesn’t hold up anymore. A 2008 study showed that people’s medical history doesn’t predict what strain they have. Someone who got MRSA from a gym might carry a hospital-type strain. Someone in the hospital might have a community strain from their kid’s soccer team.

Researchers now say we need to stop thinking of CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA as separate. They’re part of one big, messy ecosystem. Antibiotics used in hospitals select for resistant strains. Antibiotics used in the community - even over-the-counter creams or leftover pills - help those strains spread. People move between settings every day. Nurses go home. Patients go to the gym. Strains travel with them.

Mathematical models show that if community strains keep spreading, they could eventually overtake hospital strains - not because they’re stronger, but because they’re more contagious in everyday life. The balance is fragile. One change in antibiotic use - in hospitals or homes - could tip the scale.

What Can You Do? Prevention in Real Life

There’s no magic shield against MRSA. But you can reduce your risk.

- Wash hands often - especially after touching shared equipment, before and after wound care, and after using public showers.

- Don’t share towels, razors, or athletic gear. Even clean-looking items can carry bacteria.

- Keep cuts clean and covered. A small scrape can become an abscess if infected.

- If you’re in a high-risk setting - prison, military, homeless shelter - ask about cleaning protocols. Sanitation matters.

- Never use leftover antibiotics. Finishing a course wrong helps resistant strains survive.

- If you have a skin infection that’s red, hot, swollen, and getting worse fast - see a doctor. Don’t wait. Drainage might be all you need.

And if you’re visiting someone in the hospital? Wash your hands before and after. Don’t touch IV lines or wounds. Ask staff if they’ve washed their hands. It’s not rude - it’s necessary.

The Future: Surveillance and Strategy

Health systems are waking up. Some hospitals now test all incoming patients for MRSA, not just those with a history. Labs are using genetic sequencing to track which strains are moving where. Public health agencies are starting to monitor MRSA in communities - not just hospitals.

But the real fix? Changing how we use antibiotics. In hospitals, we need better stewardship - only using powerful drugs when absolutely needed. In the community, we need to stop treating every pimple with antibiotics. And we need better hygiene in crowded living spaces.

MRSA isn’t going away. But we can slow it down. By understanding how it moves - from gym mats to hospital beds, from drug users to nurses’ hands - we can break the chain. It’s not about fear. It’s about smart action.

Can MRSA be cured completely?

Yes, most MRSA infections can be cured. Skin infections often heal with drainage alone. Antibiotics like clindamycin or Bactrim work well for community strains. Hospital strains may require stronger IV drugs like vancomycin. Even after treatment, some people remain carriers - meaning the bacteria live on their skin or in their nose without causing illness. Decolonization protocols (like nasal ointments and special soaps) can reduce this, but they don’t always work long-term.

Is MRSA contagious through the air?

Not typically. MRSA spreads through direct contact - touching infected skin, contaminated surfaces, or sharing personal items. The only exception is necrotizing pneumonia caused by CA-MRSA, where the bacteria can spread in respiratory droplets. But this is rare. For most cases, airborne transmission isn’t a concern. Focus on hand hygiene and avoiding skin contact with open wounds.

Can you get MRSA from a pet?

Yes, but it’s uncommon. Pets - especially dogs and cats - can carry MRSA, usually from their human owners. If a pet has a skin infection and you touch it, you could get infected. The reverse is also true: humans can pass MRSA to pets. Good hygiene after handling sick animals reduces risk. Routine pet MRSA screening isn’t recommended unless there’s a known outbreak or recurrent infections in the household.

Why do some people keep getting MRSA infections?

Recurrent infections usually mean the bacteria never fully left. You might be a carrier - MRSA hiding in your nose or on your skin. Or your environment is still contaminated - shared towels, dirty gym equipment, or a household member who’s asymptomatic. Some people have weakened immune systems or skin conditions like eczema that make them more vulnerable. If you get MRSA more than once, you need testing to find the source - and possibly decolonization treatment.

Does MRSA show up in routine blood tests?

No. Routine blood tests like CBC or metabolic panels won’t detect MRSA. To confirm it, doctors need a culture - swabbing a wound, blood, or nasal secretions and growing the bacteria in a lab. Newer tests can identify MRSA DNA in hours, but they’re not part of standard screening unless there’s a reason to suspect infection. If you have a suspicious skin lesion, ask for a culture - don’t assume it’s MRSA without testing.

Are natural remedies like honey or tea tree oil effective against MRSA?

Some studies show medical-grade honey (like Manuka) has antibacterial properties and may help heal minor skin infections when used alongside standard care. Tea tree oil has shown some effect in lab tests, but it’s not reliable for treating active MRSA. Neither replaces antibiotics or drainage for serious infections. Using them alone can delay proper treatment and let the infection spread. Always consult a doctor before trying alternatives.

MRSA isn’t a monster. It’s a bacteria that evolved to survive our tools. The more we understand how it moves between hospitals and homes, the better we can stop it. It’s not about perfection - it’s about awareness, hygiene, and smart choices.

Comments (11)