Every year, millions of people take medications that can silently damage their hearing. Many don’t know it until it’s too late. The drugs saving their lives - antibiotics for severe infections, chemotherapy for cancer, even some antidepressants - can also destroy the delicate hair cells in the inner ear. Once gone, those cells don’t come back. Hearing loss from these medications isn’t rare. It’s common, predictable, and often preventable.

What Exactly Are Ototoxic Medications?

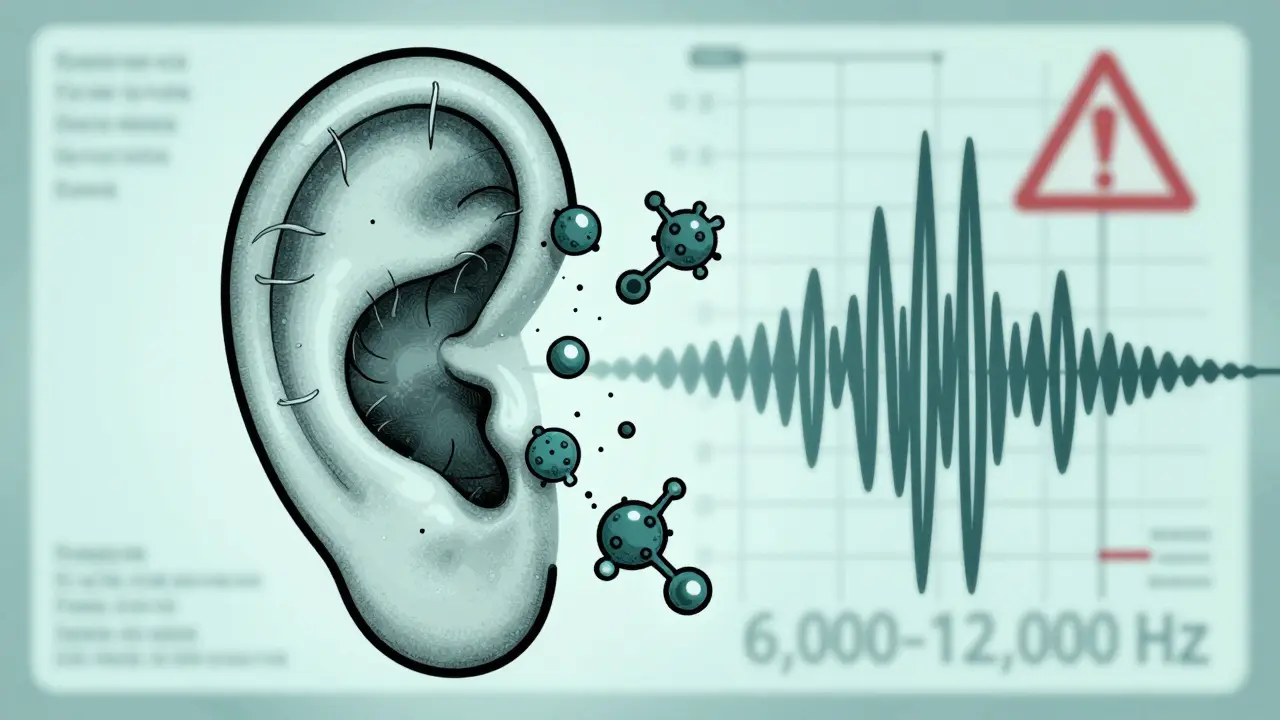

Ototoxic means "ear poisoning." These are drugs that damage the inner ear, especially the cochlea and vestibular system. The damage isn’t always immediate. Sometimes it starts with a high-pitched ringing in the ears - tinnitus - before hearing begins to fade. Other times, it shows up as dizziness or trouble balancing. The worst part? Standard hearing tests often miss it. The inner ear has tiny hair cells that turn sound waves into electrical signals for the brain. Ototoxic drugs kill these cells. Once they’re gone, the hearing loss is permanent. Over 600 prescription medications are known to carry this risk, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. That includes common drugs like gentamicin, cisplatin, and even some SSRIs like sertraline.The Worst Offenders: Cisplatin and Aminoglycosides

Not all ototoxic drugs are created equal. Two classes stand out as the most dangerous:- Cisplatin - A chemotherapy drug used for lung, ovarian, and testicular cancers. Between 30% and 60% of patients develop hearing loss. For kids, it’s even worse - up to 35% experience delays in language development because their hearing loss wasn’t caught early. Cisplatin doesn’t just damage during treatment. It sticks around in the inner ear for months, slowly killing more cells after the last dose.

- Aminoglycosides - Antibiotics like gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin. Used for life-threatening infections like sepsis or drug-resistant tuberculosis. Up to 63% of patients on long-term treatment lose hearing. In places like Cape Town, where TB is still a major health issue, this is a huge concern. These drugs are cheap and effective, but they come at a steep cost: permanent tinnitus or deafness.

How the Damage Happens

These drugs don’t just randomly hurt your ears. They attack in specific ways:- Oxidative stress - Cisplatin and aminoglycosides flood the inner ear with free radicals. These unstable molecules tear apart cell membranes and DNA.

- Blocked blood flow - Some drugs reduce circulation to the cochlea, starving hair cells of oxygen.

- Direct toxicity - The drugs bind to hair cells and trigger self-destruction.

- Neurotransmitter interference - Certain antidepressants mess with chemical signals in the inner ear, disrupting hearing.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. Your body matters too:- Genetics - A single mutation in mitochondrial DNA (m.1555A>G) makes people 100 times more likely to go deaf from aminoglycosides. It’s rare, but if your family has a history of hearing loss after antibiotics, you should know.

- Age - Older adults have fewer hair cells to begin with. One hit can push them over the edge.

- Kidney function - Aminoglycosides are cleared by the kidneys. If your kidneys are weak, the drug builds up. More exposure = more damage.

- Dose and duration - The longer you’re on the drug, the worse it gets. Cisplatin’s risk climbs with each cycle. Gentamicin given for more than 7 days? Risk jumps dramatically.

Monitoring: The Only Way to Catch It Early

The good news? You can stop this before it ruins your life. But you have to ask for it. Standard audiograms? Not enough. You need high-frequency audiometry - testing up to 8,000 or even 12,000 Hz. This isn’t offered at every clinic. You have to request it. Here’s what real monitoring looks like:- Baseline test - Before starting cisplatin or gentamicin, get a full hearing test that includes high frequencies.

- Regular follow-ups - After each cisplatin cycle. After every 3-5 doses of gentamicin. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Otoacoustic emissions (OAE) - This test listens to the inner ear’s own sounds. It can detect hair cell damage before you even notice hearing loss. It’s faster, painless, and 25% more sensitive than regular audiometry.

- Vestibular testing - If you feel dizzy or unsteady, ask for balance tests. Aminoglycosides don’t just hurt hearing - they wreck your inner ear’s balance system.

What Patients Are Saying

Real stories show why this matters:- A 12-year-old boy on cisplatin for neuroblastoma started having trouble in school. He wasn’t responding when called. His teacher thought he was daydreaming. His hearing test showed profound loss at 8,000 Hz - missed by his school’s standard test. He now uses hearing aids and speech therapy.

- A woman in Johannesburg got gentamicin for a UTI. Three weeks later, she couldn’t sleep. The ringing in her ears was constant. She didn’t know it was from the drug. Her audiologist confirmed permanent damage. She’s now on disability.

- A Reddit user wrote: "My oncologist said, ‘We don’t check hearing unless you complain.’ I didn’t complain because I thought it was stress. By the time I got tested, I’d lost 70% of my high-frequency hearing. It’s gone forever."

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Progress is slow, but it’s happening:- In 2022, the FDA approved sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark) to protect kids’ hearing during cisplatin treatment. In trials, it cut hearing loss by 48%.

- Researchers are testing N-acetylcysteine - an antioxidant - to shield hair cells from aminoglycosides. Early results are promising.

- Smartphone apps are being developed to test high-frequency hearing at home. One study showed these apps could detect changes with 90% accuracy.

- WHO and ASHA now recommend routine monitoring for all patients on high-risk drugs. But only 45% of U.S. cancer centers follow the guidelines.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re about to start a high-risk medication:- Ask your doctor: "Is this drug ototoxic?" If yes, ask for a baseline high-frequency hearing test.

- Insist on follow-up tests at key points in treatment. Don’t wait for symptoms.

- Get an OAE test if available. It’s quick and catches damage early.

- Track your own hearing. If you start hearing ringing, buzzing, or muffled sounds - especially in quiet rooms - tell your care team immediately.

- If you’re on long-term antibiotics or chemotherapy, ask for a referral to an audiologist who specializes in ototoxicity.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about individual patients. In the U.S. alone, medication-induced hearing loss costs over $1 billion a year in hearing aids, therapy, and lost work. In low-resource areas, where TB and sepsis are common, it’s a silent epidemic. We have the tools to stop it. We just need to use them. The science is clear. The solutions exist. What’s missing is awareness - and the will to act.Can ototoxic hearing loss be reversed?

No. Once the hair cells in the inner ear are destroyed, they don’t regenerate. This is why early detection is critical - you can’t fix the damage, but you can stop it from getting worse. Stopping the drug early, using protective agents like sodium thiosulfate, or adjusting the dose can preserve what hearing you still have.

Do all antibiotics cause hearing loss?

No. Only certain classes are ototoxic. Aminoglycosides like gentamicin and amikacin are the biggest risk. Vancomycin, penicillin, and azithromycin carry very low or no risk. Always ask which antibiotic you’re being given and whether it’s known to affect hearing.

Is it safe to take ibuprofen or aspirin if I’m worried about hearing loss?

High doses of NSAIDs like ibuprofen or aspirin can cause temporary hearing changes or tinnitus - but it’s usually reversible when you stop taking them. This is different from permanent damage caused by cisplatin or aminoglycosides. Still, if you notice ringing in your ears after starting a new painkiller, talk to your doctor.

Why don’t doctors test hearing before starting chemo?

Many don’t know the guidelines. Others assume patients will report symptoms. But hearing loss from cisplatin often starts silently - at frequencies standard tests don’t check. Patients may not realize their hearing is fading until it’s too late. That’s why proactive testing is essential. If your oncologist doesn’t offer it, ask for an audiologist referral.

Can genetic testing prevent ototoxic hearing loss?

For some people, yes. A simple genetic test can detect the m.1555A>G mutation that makes you extremely sensitive to aminoglycosides. If you have this mutation, doctors can avoid those drugs entirely. But testing isn’t routine yet because it’s expensive and the mutation is rare. If you have a family history of hearing loss after antibiotics, ask about genetic screening.

Are children more at risk than adults?

Yes. Children’s ears are still developing, and their blood-labyrinth barrier is more permeable. Cisplatin can cause permanent hearing loss in up to 60% of pediatric cancer patients. This can delay speech, language, and learning. That’s why pediatric oncology centers are now required to monitor hearing closely - and why sodium thiosulfate was approved specifically for kids.

Next Steps If You’re on Ototoxic Medication

- If you’re starting treatment - Schedule a high-frequency audiogram before your first dose. Write down the results.

- If you’re already on treatment - Request a hearing test now. Don’t wait for symptoms. Even one missed test could mean the difference between mild and severe loss.

- If you’ve had hearing loss - Get a referral to an audiologist for hearing aids or cochlear implants if needed. Support groups exist - you’re not alone.

- If you’re a caregiver - Learn the signs: turning up the TV, asking people to repeat themselves, avoiding quiet rooms, complaining of ringing. These aren’t just "getting older" - they could be drug damage.

Comments (15)