Tetracycline Effectiveness Calculator

Effectiveness Assessment

Based on current resistance patterns and patient factors

Key Factors

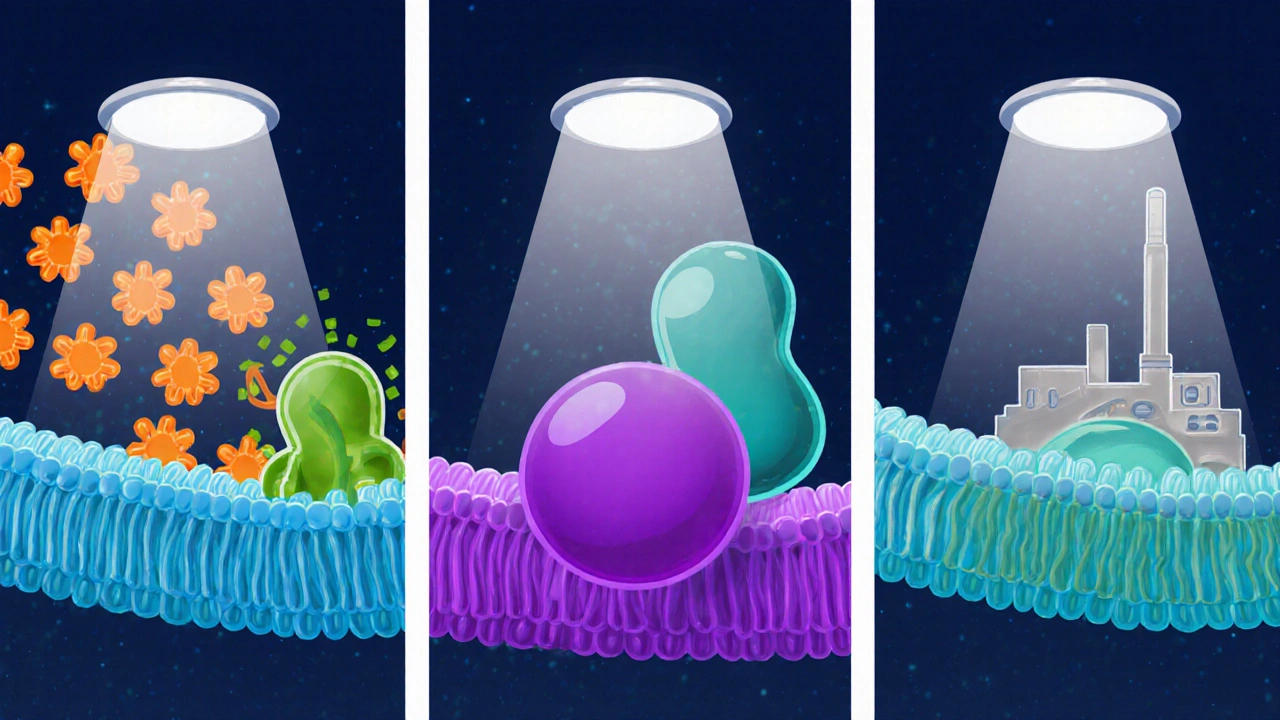

Tetracycline is a broad‑spectrum antibiotic that has been used since the 1950s to treat a variety of infections. Its ability to halt bacterial growth lies in a precise molecular trick: it blocks the machinery that makes proteins. Understanding the tetracycline mechanism of action helps clinicians choose the right drug, anticipate side effects, and combat resistance.

How Tetracycline Targets the Bacterial Ribosome

The central player in protein creation is the Ribosome, a complex of RNA and proteins that reads genetic instructions. In bacteria, the ribosome consists of two subunits: the smaller 30S subunit and the larger 50S subunit.

Tetracycline binds reversibly to a pocket on the 30S subunit. This pocket normally holds the aminoacyl‑tRNA during the elongation phase of protein synthesis. By occupying that site, tetracycline physically blocks the incoming tRNA, preventing it from adding its amino acid to the growing peptide chain.

Consequences of Blocking Aminoacyl‑tRNA Binding

When the ribosome can’t accept new tRNAs, the elongation cycle stalls. The bacterial cell can’t produce essential enzymes, structural proteins, or transporters, and its growth halts. Because the effect is bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal, the drug relies on the immune system to clear the weakened organisms.

This mode of action is distinct from beta‑lactams (which break cell walls) or fluoroquinolones (which cut DNA replication). Tetracycline’s focus on the translation step makes it effective against a range of both Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as atypical organisms like mycoplasma and chlamydia.

Spectrum of Activity: Who Gets Hit?

The drug’s ability to cross bacterial membranes gives it a wide coverage. Typical targets include:

- Staphylococcus aureus (including some MRSA strains)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Rickettsia spp.

Because it does not rely on cell‑wall synthesis, it remains active where beta‑lactams fail, especially against intracellular pathogens that hide inside host cells.

Pharmacokinetics at a Glance

Tetracycline is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (about 60‑80 % oral bioavailability). Food, especially calcium‑rich dairy, can lower absorption, so the drug is usually taken on an empty stomach. Once in the bloodstream, it distributes widely, accumulating in bone, teeth, and inflamed tissues. The drug is primarily excreted unchanged by the kidneys, with a half‑life of roughly 6-8 hours in adults with normal renal function.

How Bacteria Fight Back: Resistance Mechanisms

Unfortunately, bacteria have evolved several ways to dodge tetracycline’s grip.

- Efflux pumps: Transport proteins push the antibiotic out of the cell before it can reach the ribosome. Genes such as tetA and tetB encode these pumps.

- Ribosomal protection proteins: Proteins like TetM slide onto the ribosome and change its conformation, dislodging tetracycline without breaking the translation process.

- Enzymatic inactivation: Some bacteria produce enzymes that chemically modify the drug, rendering it inactive.

These mechanisms can be plasmid‑borne, allowing rapid spread between species. The rise of multidrug‑resistant strains makes it crucial to use tetracycline judiciously and reserve it for infections where alternatives are limited.

Side Effects and Clinical Considerations

Because tetracycline chelates calcium, prolonged use can cause teeth discoloration in children and bone growth inhibition. Common adverse events include nausea, photosensitivity, and a metallic taste. Patients with liver or kidney impairment may need dose adjustments, and the drug is contraindicated in pregnancy.

Therapeutic monitoring is rarely needed for standard doses, but clinicians should watch for signs of superinfection (e.g., Clostridioides difficile) and counsel patients about sun protection.

Comparison Within the Tetracycline Family

| Attribute | Tetracycline | Doxycycline | Minocycline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Half‑life (hours) | 6‑8 | 12‑25 | 11‑22 |

| Oral bioavailability | 60‑80 % | ≈95 % | ≈90 % |

| Food effect | Reduced with dairy | Minimal | Minimal |

| Common uses | Acne, rickettsial disease | Lyme disease, malaria prophylaxis | Severe acne, CNS infections |

| Typical side‑effects | Nausea, photosensitivity | Less GI upset, still photosensitive | Dizziness, vestibular issues |

All three bind the same ribosomal site, but differences in pharmacokinetics and tolerability guide drug choice. Doxycycline’s longer half‑life allows once‑daily dosing, while minocycline’s higher lipophilicity makes it useful for central nervous system infections.

Practical Tips for Clinicians

- Prescribe the shortest effective course to limit resistance pressure.

- Advise patients to avoid dairy, antacids, and iron supplements within two hours of dosing.

- Check renal function before dosing elderly patients; reduce dose if creatinine clearance <30 mL/min.

- Consider switching to doxycycline or minocycline for infections requiring longer therapy, due to better tolerability.

- Monitor for photosensitivity; recommend sunscreen and protective clothing.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does tetracycline differ from penicillin?

Penicillin attacks bacterial cell‑wall synthesis, killing the cell. Tetracycline blocks protein synthesis on the ribosome, stopping growth without outright killing the bacteria.

Can tetracycline be used in children?

Generally no. It can cause permanent teeth discoloration and affect bone growth in children under eight years old. Doxycycline is sometimes used in older kids when benefits outweigh risks.

What are the most common resistance genes?

The tetA, tetB (efflux) and tetM (ribosomal protection) genes dominate. They are often located on plasmids that spread between species.

Is it safe to take tetracycline with calcium supplements?

No. Calcium binds tetracycline in the gut, cutting absorption by up to 50 %. Separate the doses by at least two hours.

Why does tetracycline cause photosensitivity?

The drug accumulates in skin cells and, when exposed to UV light, generates reactive oxygen species that damage skin, leading to sunburn‑like reactions.

When should doxycycline be preferred over tetracycline?

For longer courses, once‑daily dosing, or when food‑related absorption issues are a concern, doxycycline’s higher bioavailability and longer half‑life make it the better choice.

Comments (11)