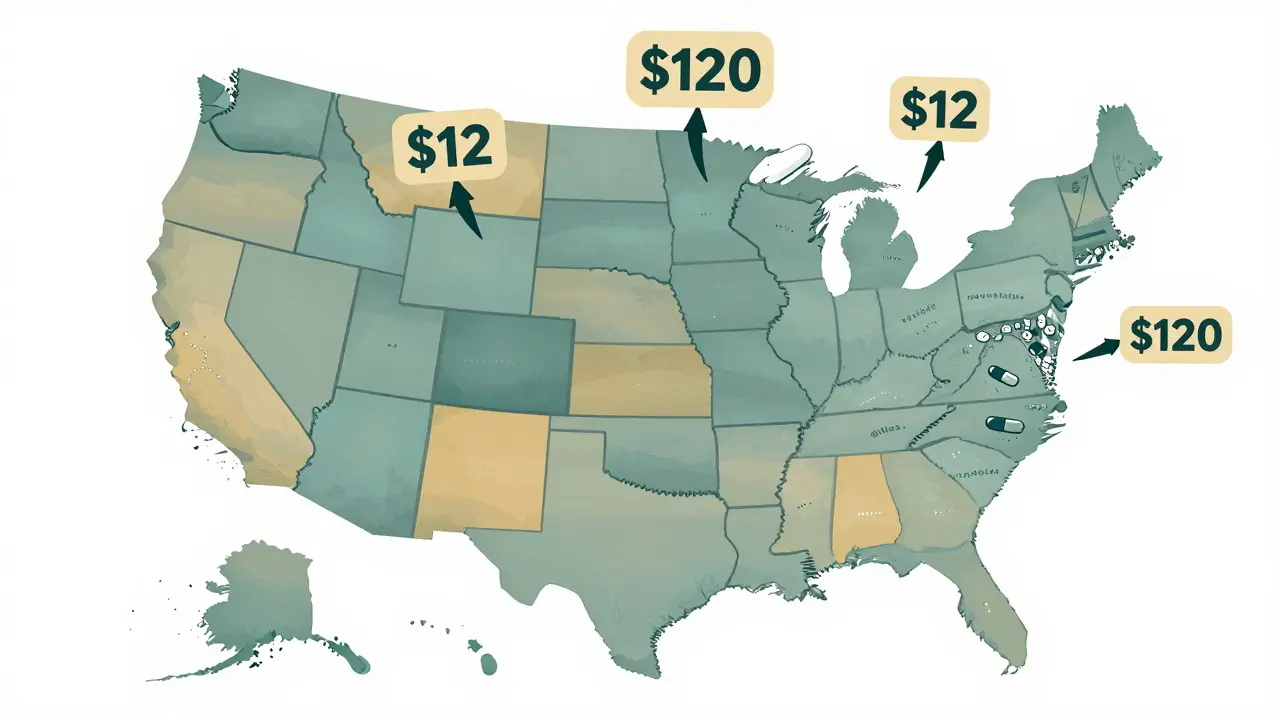

Have you ever filled a prescription for a generic drug and been shocked by the price-only to find out your neighbor down the street paid less than half for the same pill? It’s not a mistake. It’s not fraud. It’s just how the system works. In the United States, the cost of a generic medication like atorvastatin or metformin can swing from $12 to $120 depending on which state you live in. And it’s not just about insurance. Sometimes, paying cash saves you more than using your plan. This isn’t random. It’s the result of a tangled web of state laws, pharmacy benefit managers, market competition, and hidden markups that vary wildly from one border to the next.

How One Pill Can Cost 10 Times More in One State

Take a 90-day supply of generic atorvastatin, the cholesterol-lowering drug. In California, a patient with insurance might pay $45. In Texas, under a different PBM contract, the same prescription could cost $120. That’s not a typo. That’s a 167% difference for the exact same medicine. And this isn’t an outlier. GoodRx data from 2022 showed price swings of up to 300% for identical generics between neighboring states. Why? Because pricing isn’t set by the manufacturer. It’s set by middlemen.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs, act as intermediaries between drug manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies. They negotiate rebates, set formularies, and determine what you pay at the counter. But here’s the catch: they don’t have to show you how they calculate those prices. In states with weak transparency laws, PBMs can mark up the cost of generics without accountability. In states like California and Maryland, where laws require more disclosure, prices tend to be lower-often 8% to 12% cheaper on average for the same drug.

Why Medicaid and Cash Pay Are Two Different Worlds

Medicaid, the government health program for low-income Americans, sets reimbursement rates for generic drugs differently in every state. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which updates monthly based on a three-month moving average. Others use outdated benchmarks or private contracts. That means two identical pharmacies in two neighboring states might get paid completely different amounts for the same pill. And since pharmacies need to cover their costs, they pass those differences onto patients.

Here’s where it gets even stranger. If you pay cash, you often pay less than if you use insurance. A 2022 USC Schaeffer Center study found that out-of-pocket payments for generics dropped by nearly half when patients skipped insurance entirely. Why? Because insurance plans sometimes have high copays that are based on inflated list prices. The actual cost the pharmacy pays might be $5, but your plan’s contract with the PBM says you owe $30. Paying cash lets you access the pharmacy’s real wholesale price-often the same price Medicare pays. That’s why services like GoodRx and Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company are booming. In 2020, 4% of all U.S. prescriptions were paid in cash-and 97% of those were for generics. That’s not a fluke. It’s a workaround built into a broken system.

State Laws Tried to Fix This. Then the Courts Stepped In

Between 2016 and 2018, more than 100 state bills aimed at controlling drug prices were introduced. Vermont led the way with transparency laws. California followed with rules forcing PBMs to report pricing data. Maryland went further-it passed a law specifically banning generic drug price gouging. For a moment, it looked like states were finally taking control.

Then came the federal court ruling in 2018. A federal appeals court struck down Maryland’s law, saying it violated the Constitution’s Commerce Clause. The court decided states couldn’t regulate prices that moved across state lines. That decision sent a chill through state legislatures. Nevada’s attempt to cap diabetes drug prices was dropped. Other states paused their efforts. The message was clear: if you try to cap prices directly, you’ll get sued. So states shifted tactics. Today, 18 states have created drug affordability boards that review pricing trends and recommend action-but they can’t force manufacturers or PBMs to lower prices. They can only study them.

Why Rural Areas Pay More

It’s not just about state lines. It’s about how many pharmacies serve your zip code. In rural areas, there might be one pharmacy. In cities, there are five. Competition drives prices down. No competition? Prices stay high. A Medicare claims analysis showed patients in states with fewer pharmacies paid 15-20% more for generics-even within the same state. That’s why someone in rural West Virginia might pay $60 for metformin while someone in Chicago pays $25. It’s not about income. It’s about access.

And it’s not just rural. Even in big cities, pharmacy deserts exist. In low-income neighborhoods, chains may avoid opening stores. Independent pharmacies struggle to stay open. Without competition, they can’t negotiate better wholesale rates. So they charge more. And patients have no choice but to pay it.

The Inflation Reduction Act Didn’t Fix This

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 brought big changes-for Medicare Part D users. It capped insulin at $35 a month. It capped total out-of-pocket spending at $2,000 a year starting in 2025. These are huge wins. But here’s the catch: they only apply to Medicare beneficiaries. That’s 32% of U.S. drug spending. What about the other 68%? People with private insurance? The uninsured? Those on Medicaid? For them, the rules haven’t changed much.

The Act also requires drugmakers to pay rebates if they raise prices faster than inflation. But that only applies to brand-name drugs, not generics. And even then, it doesn’t touch the PBM markups that happen after the drug leaves the factory. So while the cost of a brand-name drug might stabilize, the cost of its generic cousin can still jump 15% in a year-just like 1,982 other generic drugs did between January 2022 and January 2023, according to ASPE data. The average price increase? $590 per drug. And no state law can stop it.

What You Can Do Right Now

Here’s the truth: you can’t change the system. But you can work around it. And it’s easier than you think.

- Check GoodRx or SingleCare before you pay. Type in your drug and your zip code. You’ll see cash prices from nearby pharmacies. Often, it’s cheaper than your insurance copay.

- Ask for cash pricing. Even if you have insurance, ask the pharmacist: "What’s your cash price?" Many pharmacies will give you the same price they charge Medicaid.

- Switch pharmacies. If your local pharmacy charges $80 for a generic, try the one across town. Or try a warehouse club like Costco. Their generic prices are often 30-50% lower.

- Use mail-order for maintenance drugs. If you take the same pill every month, order a 90-day supply. Many insurers offer discounts for mail-order. And if you pay cash, you might save even more.

- Know your state’s laws. If you live in California, New York, or Maine, you have more tools. These states require PBMs to disclose pricing. Use that. Ask for reports. File complaints. Demand transparency.

And if you’re lucky enough to live in a state with a drug affordability board, attend a meeting. Speak up. These boards are still new. They’re listening. Your voice matters.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they only account for 18% of total drug spending. That sounds good-until you realize that patients still pay billions extra because of opaque pricing. The problem isn’t that generics are expensive. It’s that the system is designed to hide how much they really cost.

Manufacturers don’t set these prices. PBMs do. Pharmacies do. Insurers do. And states? They’re stuck in a legal gray zone. Until federal law steps in to standardize pricing transparency, the differences will keep growing. One state will lower costs. Another will let them soar. And patients? They’ll keep shopping around, paying cash, and wondering why the same pill costs so much more in their town.

It’s not fair. But it’s real. And now, you know how to beat it.

Why do generic drug prices vary so much between states?

Generic drug prices vary by state because each state has different laws governing pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), Medicaid reimbursement rates, and transparency requirements. Some states require PBMs to disclose pricing, while others don’t. States also use different benchmarks to set what pharmacies are paid, which affects what patients pay out of pocket. Market competition plays a role too-areas with fewer pharmacies often have higher prices.

Can I save money by paying cash instead of using insurance for generics?

Yes, often you can. Many insurance plans have copays based on inflated list prices set by PBMs, while the actual cost the pharmacy pays is much lower. Paying cash lets you access the pharmacy’s real wholesale price, which is often 30% to 70% cheaper than your insurance copay. Services like GoodRx and Cost Plus Drug Company make this easy by showing you the lowest cash price nearby.

Why did states stop trying to cap generic drug prices?

In 2018, a federal appeals court ruled that Maryland’s law banning generic drug price gouging was unconstitutional because it interfered with interstate commerce. This decision scared other states from passing direct price caps. Now, most states focus on transparency-requiring PBMs to report pricing data-rather than setting price limits. Some states created affordability boards to study pricing, but they can’t force changes.

Does the Inflation Reduction Act help with generic drug prices?

Only for Medicare beneficiaries. The Inflation Reduction Act caps insulin at $35 a month and limits out-of-pocket spending to $2,000 a year for Medicare Part D users. But it doesn’t cap prices for generics for people with private insurance, the uninsured, or those on Medicaid. It also doesn’t regulate PBMs or pharmacy markups, which are the main drivers of price differences.

What’s the best way to find the lowest price for a generic drug in my state?

Use a price comparison tool like GoodRx or SingleCare. Enter your drug name and zip code to see cash prices at nearby pharmacies. Always ask your pharmacist for the cash price-even if you have insurance. Compare prices at chain pharmacies, warehouse clubs like Costco, and mail-order services. In states with strong transparency laws, you can also request pricing reports from your insurer or PBM.